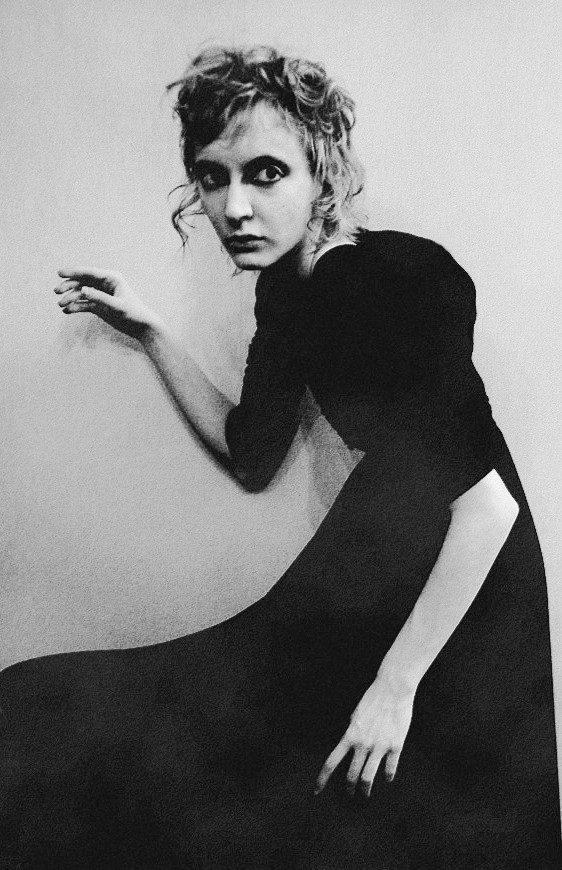

Ernst

Gombrich

19 Briardale Gardens, London NW3 7PN, United

Kingdom.

"Art is long and life is short." That famous

saying was coined more than 2,000 years ago by Hippocrates, the founder

of Greek medicine, and subsequent developments have proved him right.

For the "art" to which he refers is the art of healing that has indeed

been long in growing and developing and, in the process, incidentally,

made life gradually a little less short. In his period and long after,

the notion of art denoted any skill based on knowledge; in other words,

both what we now call "science," and what we call "art." It may

not be inappropriate to recall these origins in a journal that has set

itself the aim of bridging the rift that has meanwhile come to separate

these two branches of human creativity. It is precisely those of us who

welcome this effort who sometimes feel that artists would do well to

remember the words of Hippocrates. No scientist has to be told that any

progress at which he aims must take as its starting point the present

state of knowledge. Artists sometimes appear to hope that they can start

from scratch and create a new art by one leap of the imagination. One

may admire the ingenuity, wit and courage of such attempts, and yet feel

that this new art will remain stillborn precisely because it lacks the

background and support of a tradition. I fully realize that to

some the very word tradition is like a red rag to a

bull, but to emphasize the role of tradition---in art as well as in

science---is not tantamount to a longing for the good old days. It can

be supported by purely theoretical considerations: our aesthetic no less

than our cognitive experiences are inseparable from our expectations.

Both the thrill of surprise and the satisfaction of familiarity rest on

our previous knowledge, belief and experience. Whether we read a

scientific paper, watch a game or visit an exhibition, we can never

understand what is going on without a minimum of information previously

acquired. Learning to understand is a complex process, hard to explain

in a few words, but we all have experienced its difficulties and its

pleasures. I do not want to be misunderstood. New art forms may

certainly emerge in the future as they have emerged in the past---I am

thinking of calligraphy in China or instrumental music in the West. No

doubt, also, science and technology may still contribute to such

developments, as has indeed happened with photography and the cinema,

but in all these cases it has taken time for standards to develop and

creativity to be appreciated. It was for this reason that I concluded my

book on decoration and pattern- making, which I called The

Sense of Order, as follows: The study of the

pattern-maker's craft no less than the study of any other art suggests

that what we need is patience. It takes time for a system of conventions

to crystallize till every subtle variation counts. Maybe we would be

more likely to achieve a new language of form if we were less obsessed

with novelty and change. If we overload the system we lose the support

of our sense of order [1].

This editorial was originally published in print in Leonardo Volume

28, No. 4, which is available through the MIT Press

(journals-orders@mit.edu).

tomado de

http://www.gombrich.co.uk/showdoc.php?id=60

|